Most tax disasters don’t come from fraud.

They come from one wrong assumption.

In real estate, that assumption is usually this:

“It was my home… so it must count as my primary residence.”

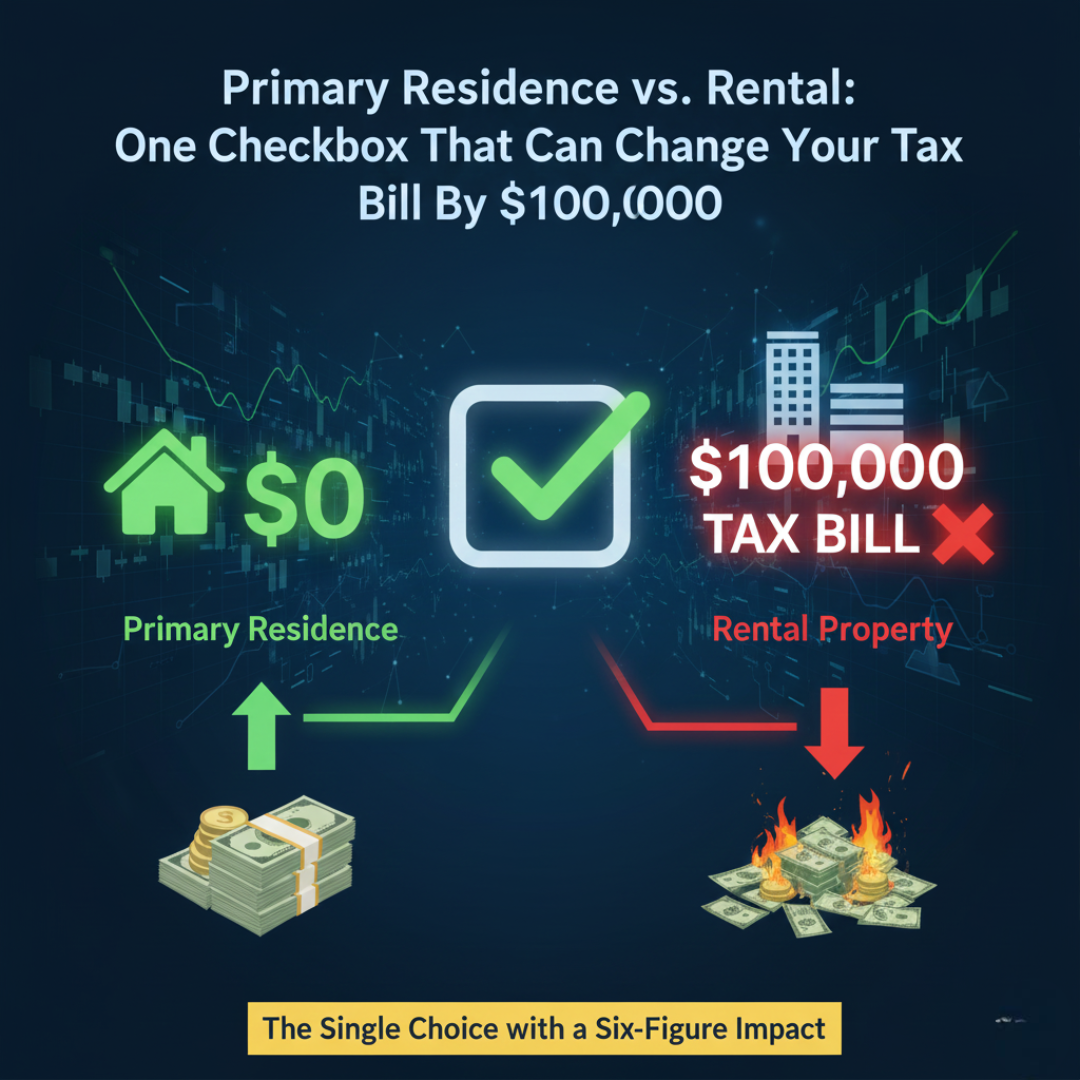

On your tax return, that belief often turns into a single checkbox. And that checkbox can decide whether you walk away tax-free — or hand six figures to the IRS.

This isn’t exaggeration. This is misclassification. And it quietly wrecks people who did everything almost right.

Why This One Detail Matters So Much

The tax code treats primary residences and rental properties like two completely different species.

Primary residence:

- Eligible for the $250,000 / $500,000 capital gains exclusion

- No depreciation recapture

- Often zero federal capital gains tax

Rental property:

- No primary residence exclusion (unless partially converted)

- Depreciation recapture at up to 25%

- Capital gains fully taxable

- Possible state tax on top

Mislabel the property, and the IRS doesn’t correct you gently. They correct you expensively.

The Checkbox That Starts the Chain Reaction

When you sell property, your tax software (or CPA) asks a deceptively simple question:

“Was this your primary residence?”

That answer determines:

- Whether the exclusion applies

- Whether depreciation must be recaptured

- How gains are categorized

- What forms get triggered behind the scenes

Check the wrong box and you either:

- Claim a tax break you don’t qualify for (audit risk), or

- Miss a tax break you absolutely did qualify for (overpayment)

Neither outcome is fun.

What the IRS Means by “Primary Residence”

The IRS doesn’t care where your heart lived.

They care where you lived.

Your primary residence is generally:

- Where you lived most of the time

- Where your mail went

- Where your driver’s license and voter registration pointed

- Where you slept, worked, and existed as a human

You don’t need to own only one home — but you can only have one primary residence at a time.

And here’s the rule that trips people up.

The 2-Out-of-5 Rule (In Plain English)

To qualify for the capital gains exclusion:

- You must own the home for at least 2 years

- You must live in it for at least 2 years

- Those 2 years must fall within the last 5 years before sale

They don’t have to be consecutive.

But they do have to be real.

Where Misclassification Happens Most Often

This is where people accidentally nuke their tax outcome.

Scenario 1: “It Used to Be My Home”

You lived in the house.

Then you moved.

Then you rented it out for a few years.

Then you sold it.

This property may still qualify partially as a primary residence — but:

- Depreciation taken during rental years must be recaptured

- The exclusion may be prorated

- Timing matters a lot

Checking “primary residence” without accounting for rental use is a common mistake.

Scenario 2: “I Lived There, Technically”

You stayed occasionally.

You kept furniture there.

But most of the time, it was rented.

The IRS doesn’t grade on vibes.

They grade on usage.

Occasional stays don’t make a rental your primary residence.

Scenario 3: “We Moved Back Before Selling”

This is the one that can save or destroy a tax bill.

Moving back into a former rental before selling can:

- Restore eligibility for the exclusion

- But not erase depreciation recapture

- And not always fully restore the exclusion

Timing and documentation decide whether this move is genius or useless.

A Real-World Tax Difference (Numbers That Hurt)

Let’s look at a simplified example.

You bought a home for $300,000.

You lived in it for 3 years.

Then rented it for 4 years.

You sell it for $650,000.

If classified carefully:

- Part of the gain may qualify for exclusion

- Depreciation is recaptured

- Tax is reduced significantly

If misclassified as purely rental:

- No exclusion

- Full capital gains tax

- Depreciation recapture

- Potential six-figure tax bill

Same house.

Same sale price.

Different checkbox.

Massive difference.

Why the IRS Cares So Much

The primary residence exclusion is one of the largest tax breaks available to individuals.

The IRS scrutinizes it accordingly.

Red flags include:

- Rental income reported in prior years

- Depreciation deductions

- Address mismatches

- Short gaps between rental use and sale

Misclassification isn’t just costly — it’s auditable.

How to Classify Correctly (Before You Sell)

Before listing a property, you should be able to answer:

- When exactly did I live here?

- When exactly was it rented?

- Was depreciation claimed?

- Do I meet the 2-out-of-5 rule?

- Does any portion qualify for exclusion?

This isn’t paperwork trivia.

This is outcome-defining math.

Internal Link Opportunity

At this point in the article, you’d naturally link to:

“Primary Residence Exemption: The Most Overlooked Tax Break for Homeowners”

to reinforce the rule and keep readers moving deeper.

Final Thought: This Isn’t a Technicality — It’s Strategy

People assume taxes punish bad behavior.

More often, they punish imprecise thinking.

Primary residence vs rental isn’t a semantic difference. It’s a classification with six-figure consequences.

Before you sell, slow down.

Check the dates.

Understand the rules.

Then check the box.

Because the IRS will.

Before you decide how to classify a property sale, it’s smart to see the numbers for yourself. Our Capital Gains Tax Calculator at CapitalTaxGain.com lets you estimate your potential tax based on purchase price, sale price, and how the property was used. Running the numbers ahead of time can help you avoid costly surprises after the sale is already done.

Leave a Reply